19 October 11

The Object of a Liberal Education

I recently added this post, The Object of a Liberal Education.

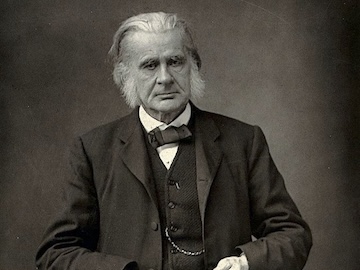

This is an extract from an address by Thomas Huxley, the eminent Victorian biologist, to the South London Working Men’s College in 1868. This was the year that the College was founded by philanthropist William Rossiter, and Huxley was speaking to the students in his capacity as the College’s first Principal. Naturally, he chose to lay before them his vision of education, and as the college leant towards the Arts, of a liberal education in particular.

Many goals have been set for education over the years. Huxley’s was unusual. He argued that life would be much smoother if people knew what Mother Nature, whose pitiless ways Huxley had come to respect in his collaboration with Charles Darwin, had in store for them. The task of teachers was to help young people realise that the secret of a happy life was to work with Nature, and not against her.

20 October 8

I recently added this post, Laughter in the House.

Sir Philip Sidney is remembered today chiefly for his selfless gesture as he lay wounded on the field of the Battle of Zutphen in 1586: see ‘Thy Necessity is Yet Greater than Mine’. But Sidney was not only a soldier and gentleman. He was a deep thinker, who wrote what is arguably the first serious work of literary criticism in the English language, An Apologie for Poetrie (ca. 1582). This was a reply to Stephen Gosson’s The School of Abuse (1579), which had been prompted by an outbreak of plague and the feeling that in such times writing plays was at best frivolous, at worst socially harmful. Gosson dedicated his tract to Sidney, an unsolicited honour that placed him in a delicate position. Ever the gentleman, Sir Philip did not name Gosson in his reply, but nevertheless came to the defence of Elizabethan drama.

That is not to say Sidney was uncritical. One of the chief targets for his mild-mannered disapproval was Elizabethan comedy. The comedians of his day took the line that anyone who got a good laugh out of a play must be the better for the experience, but Sidney made an extremely important distinction between laughter and delight, noting that laughter is often produced by very unworthy things.

21 October 8

I recently added this post, Heracles and Omphale.

E. M. Berens was an American writer who published several books on Greek and Roman mythology, intended for casual readers and particularly for children. In his preface, he declares “that no pains have been spared in order that without passing over details the omission of which would have marred the completeness of the work, not a single passage should be found which could possibly offend the most scrupulous delicacy”. For many of the Greek myths, this is a challenging goal to set, and the story of Heracles and Omphale, the delectable Queen of Lydia, must have given Berens some pause. Happily, he judged the scrupulosity of American boys and girls to be sufficiently resilient to deal with the mental image of Omphale wearing a lionskin and Heracles in a dress.

22 October 5

I recently added this post, The Perils of the Learned.

Al-Ghazali (1056-1111), known in Mediaeval Europe as Algazel, was one of the towering figures of Islam at around the time of Anselm of Canterbury in England. In 1091, Al-Ghazali (who was from Tus, now Tous near Mashhad in Iran) was appointed to a prestigious teaching post in Baghdad, but four years later he abruptly gave it up and embarked on a ten-year pilgrimage to Damascus, Jerusalem and Mecca, his faith in academe shaken by the intrigues of Court and University alike. The fruit of his soul-searching was The Revival of the Religious Sciences, in which he examined what the search for knowledge should be like for the truly religious man.

This short extract finds Al-Ghazali canvassing the views of various Muslim authorities on the dangers of learning. It includes a neat aphorism by Al-Khalil ibn-Ahmad (?718-?791), compiler of the first Arabic dictionary, which in various forms may be found in English books of quotations, and which NL Clay set as a test of elocution:

He who knows and knows that he knows,

Is wise; follow him.

He who knows and knows not that he knows,

Is asleep; wake him.

He who knows not and knows not that he knows not,

Is a fool; shun him.

He who knows not and knows that he knows not,

Is a child; teach him.

Al-Ghazali’s views on education are quite well summed up by another English writer, William Hornbye, who wrote in his Horn-Book (1622):

Learning’s a ladder, grounded upon faith

By which we clime to heaven (the Scripture saith);

And ’tis a means to hurry men to hell

If grace be wanting for to use it well.

23 October 1

I recently added this post, The Black Rood of Scotland.

It comes from The Rites of Durham, a look back at the abbey at Durham Cathedral as it was before the Protestant Reformation that began with Henry VIII’s break with Rome in 1534. The Rites was written by an anonymous author in 1593; however, for this extract I have used an edition made in 1671, because it has more modern spelling and vocabulary.

This particular passage has to do with the Battle of Neville’s Cross, in which English forces repelled a Scottish invasion on October 17th, 1346, at Redhills just west of Durham. King David II of Scotland carried a priceless relic, the Black Rood, into the battle. The author of the Rites recounts the legend of how David came to possess it, and then goes on to tell us what happened to it after the battle, and why.

Composition

Join each group of ideas together into one sentence in at least two different ways, using different words as much as you can.

1 David fought in the Battle of Neville’s Cross. He wore the Black Rood on his breast. He hoped it would protect him.

2 A stag menaced David. He raised his hands. A cross appeared in them. The stag vanished.

3 David built an abbey. He put the Black Rood in it. He named the abbey Holyrood.

24 September 27

I recently added this post, Infirm of Purpose!.

It is an extract from William Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth, seen by Dr Forman on April 20th, 1611, but probably first performed for King James I some five years earlier.

The basic premise of the play is that Duncan I, King of Scots, was murdered in his bed by his nephew Macbeth in AD 1040. In fact, Macbeth gained Duncan’s crown in battle, not by assassination, but Shakespeare’s version of the events lends itself better to the stage. In this extract, we see him stumbling back to his chamber after doing the grisly deed, already entering a state bordering moral collapse as he thinks about what he has done. His wife, Lady Macbeth, tries to keep him focused — the murder weapons have to be disposed of properly, and Duncan’s blameless servants have to be incriminated — but Macbeth is frankly losing his grip.

Composition

Join each group of ideas together into one sentence in at least two different ways, using different words as much as you can.

1 Macbeth murdered Duncan. He felt bad about it.

2 Macbeth’s hands were bloody. It upset him. Lady Macbeth called him foolish.

3 Duncan’s servants were asleep. Lady Macbeth incriminated them. She put blood on them.